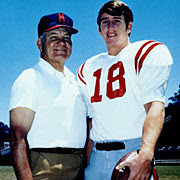

Even more significantly, Vaught’s six conference titles are the only ones Ole' Miss has ever won. Until the second coming Manning in the form of Eli, chances are that anything you know about the entire history of Rebel football happened with Vaught on the sideline.

Vaught grew up in Olney, Texas before moving to Fort Worth to live with his grandmother and attend Polytechnic Heights High School. He played his first varsity prep football game against Poly’s local rival, the legendry Masonic Home “Mighty Mites.” Poly lost 40-0. Vaught learned a lot about grit, resolve and team psychology from Poly’s frequent bouts with Masonic Home (which the Mites generally won despite considerable disadvantages in size and manpower).

Vaught worked as a line coach at North Carolina in the late 1930s when the Tar Heels were a national power. He served in the Navy during WWII and took the Mississippi job after the 1946 season. He would never coach anywhere else. The 1946 Rebels had finished a woeful 2-7. One year later Vaught’s first team finished 9-2, went undefeated in conference play and won the SEC for the first time in school history. Vaught brought a new attitude to Oxford. He was serious about football, a thinking coach and a winner. His first act as head coach was to order the state highway department to dig a new practice field in an eight-foot pit. He surrounded the pit with trees and campus cops and went to work. Vaught’s practices were always secret, and with good reason. His flexible strategic approach to offensive planning was, like Schmidt and Meyer at TCU, years ahead of the times. Vaught routinely surprised opponents who looked far more talented on paper.

The most famous example of Vaught’s coaching genius came in November 1969 at Tennessee against Doug Dickey’s undefeated, top-ranked Volunteers. Vaught’s underrated Rebels were 5-3, but had taken all their losses on the road and two of them by a single point each. Junior quarterback Archie Manning had amassed 1,394 yards and 6 TDs on 128 completions in 222 attempts. He had also run for 363 yards on 100 carries with 11 TDs. Despite Manning's impressive stats Tennessee’s all-American linebacker Steve Kiner brashly called Mississippi’s players “mules” in an interview several weeks prior to the season. Tennessee fans, supremely confident in their team, compounded the insult by wearing buttons reading “Archie who?” Someone even found the spare cash to pay for a small plane to fly over Mississippi’s practice field and drop leaflets reading “Archie mud”. Naturally common opinion in Mississippi was that an unknown Vol backer had paid for the stunt, but no one ever claimed credit and at least one Rebel beat writer suspected that Vaught had organized it himself in order to rile up his players.

The most famous example of Vaught’s coaching genius came in November 1969 at Tennessee against Doug Dickey’s undefeated, top-ranked Volunteers. Vaught’s underrated Rebels were 5-3, but had taken all their losses on the road and two of them by a single point each. Junior quarterback Archie Manning had amassed 1,394 yards and 6 TDs on 128 completions in 222 attempts. He had also run for 363 yards on 100 carries with 11 TDs. Despite Manning's impressive stats Tennessee’s all-American linebacker Steve Kiner brashly called Mississippi’s players “mules” in an interview several weeks prior to the season. Tennessee fans, supremely confident in their team, compounded the insult by wearing buttons reading “Archie who?” Someone even found the spare cash to pay for a small plane to fly over Mississippi’s practice field and drop leaflets reading “Archie mud”. Naturally common opinion in Mississippi was that an unknown Vol backer had paid for the stunt, but no one ever claimed credit and at least one Rebel beat writer suspected that Vaught had organized it himself in order to rile up his players.Dietzel grew up in Fremont, Ohio. He played one year of college ball at Duke before joining the U.S. Air Force for WWII. He completed his college career after the war as an all-American center at Miami, Ohio before taking assistant coaching jobs at Cincinnati, Kentucky and Army. Dietzel learned from the best in his profession, working for Paul Bryant in Lexington and Earl Blaik at West Point. When a struggling LSU hired Dietzel to his first head coaching job in 1955 the school did not gain a proven commodity, but they knew their man possessed pedigree. Even still, Dietzel’s career in Baton Rouge started slowly.

The Tigers were not the most talented southern outfit and had not fielded truly great teams in several decades. LSU posted losing seasons in 1955 and 1956, before improving to a still underwhelming 5-5 in 1957. Then Dietzel hit upon an idea that changed his fortunes. In 1953 substitution rules had been enacted which effectively restored football to a one platoon game. Coaches attempted to find the best ways around the rules, sharing talent across various units to reduce the drop off between their starters and second string. But no one came up with a more effective method than Dietzel engineered in 1958.

During pre-season drills Dietzel divided his unfancied Tigers into three units. He selected his best eleven men and designated them the first team for both offense and defense. His second eleven he designated the second string offense. For his second string defense Dietzel created a unit from mostly underclassmen and walk-ons which he named “the Chinese bandits”. Despite largely lacking talent and only playing in relief situations to keep the starters fresh, the bandits developed a feisty character, a true espirit de corps and immense popularity. Members of the unit temporarily promoted to the second string in place of injured players asked Dietzel to move them back to the bandits as soon as possible. They performed admirably, blocking punts on several occasions to give the offense prime field position. Their spirit inspired better play out of LSU’s stars, and with a first team back field featuring future Heisman Trophy winner Billy Cannon that improvement was costly to opponents.

Cannon grew up in Baton Rouge and sold peanuts at Tiger stadium as a boy. The all-American prep star had no end of scholarship offers but was only ever going to LSU. The stud lived up to his billing, gaining 512 yards in eight games as a sophomore in 1957, his first varsity season. In 1958 Cannon’s team best 686 yard on 115 carries (5.9 ypc) led LSU to an undefeated 11-0 season crowned with a 7-0 win over Clemson in the Sugar Bowl and an AP national championship. Dietzel came out of nowhere to lead the Tigers to the Promised Land, picking up Football Coaches Association coach of the year honors on the way.

LSU’s success set Cannon up for a Heisman run as a senior. Dietzel’s Tigers went 9-2 in 1959 and after a disappointing 5-4-1 campaign the following year went 10-1 in 1961 with an Orange Bowl win. Dietzel compiled a 46-24-3 record in seven seasons with three bowl appearances, a national title and a Heisman winner for his resume. Of those 24 losses only seven occurred after his first three years. For four seasons Dietzel threatened to establish LSU as a national power, but after his successful 1961 campaign accepted an offer to take over as the head coach at West Point.

On October 31st 1959 the undefeated, third ranked Rebels rolled into a hostile Halloween Baton Rouge environment for a night game in Tiger stadium. Waiting for them were Dietzel’s undefeated, top-ranked LSU. The Tigers has not lost since a home date against Mississippi State on November 16th 1957. The week before that game they had dropped a close 12-14 decision in Oxford. Paul Dietzel, Billy Cannon, the Chinese Bandits and every other Tiger did not feel like returning to the habit of losing to Ole’ Miss.

Unfortunately, the Tigers went on to lose in Knoxville the following week. That cost Dietzel a second national title as undefeated Syracuse took the AP crown behind the running of future Heisman winner Ernie Davis. The Orangemen went on to beat Texas in the Cotton Bowl while Sugar Bowl selectors took the opportunity to match the nation’s number two and three teams in a Dietzel-Vaught rematch. In the end, it seemed LSU’s magic had dried up. The Rebels won a disappointing affair easily, 21-0.

Unfortunately, the Tigers went on to lose in Knoxville the following week. That cost Dietzel a second national title as undefeated Syracuse took the AP crown behind the running of future Heisman winner Ernie Davis. The Orangemen went on to beat Texas in the Cotton Bowl while Sugar Bowl selectors took the opportunity to match the nation’s number two and three teams in a Dietzel-Vaught rematch. In the end, it seemed LSU’s magic had dried up. The Rebels won a disappointing affair easily, 21-0.