In the modern era college football’s premier award has evolved into a media driven runaway-train. Every season begins with one or two clear favorites, decided on publicity power and the record of program he represents as much as individual talent. As of 2008, ten schools have claimed 14 of the last 16 Heisman trophies: Notre Dame, USC, Texas, Oklahoma, Nebraska, Ohio State, Michigan, Miami, Florida and Florida State. These are the schools with the most wins and/or greatest media draw over the last two decades. As Chris Huston will tell you, the Heisman is as much about which school a player represents as it is about the player himself. Things weren’t so different in 1956.

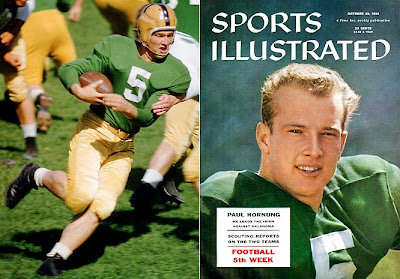

Notre Dame had gone 8-2 in 1955 under second-year head coach Terry Brennan, who despite his youthful age of only 28 reached 17-3 in two seasons. The Domers’ only losses came at the hands of 9-1 Michigan State, then enjoying their golden age under Hugh Dougherty, and on the road at USC. The memorable performances of multi-threat halfback Paul Hornung only added to expectations. As a junior the "Golden Boy" had gone 46 of 103 passing for 743 yards and a 9-10 ratio, in addition to carrying 92 times for 472 (a 5.1 yard average) and 6 TDs. Hornung also kicked 5 PATs and 2 field goals. Heading into the fall of 1956 Hornung had name recognition, impressive stats, played for a winning team expected to improve, and possessed limitless personal appeal. He was boyishly handsome, devilishly cocky and irresistibly talented. But most of all, he played for Notre Dame. Sports writers in the mid-fifties loved the Irish with abandon. So in early September, the Heisman seemed to be Hornung’s to lose.

Hornung competed against probably the largest and most talented crowd of Heisman hopefuls ever. Down in Knoxville, standout Tennessee halfback Johnny Majors led the Vols to an unbeaten regular season on his way to a career total of 2,575 rushing yards. The Vols shocking upset loss to Baylor in the 1957 Sugar Bowl occurred after the voting, in which Majors polled second. Five places behind him, the nation’s leader in total offense, Stanford’s John Brodie, gained only gained enough votes to come in a lowly seventh!

Hornung competed against probably the largest and most talented crowd of Heisman hopefuls ever. Down in Knoxville, standout Tennessee halfback Johnny Majors led the Vols to an unbeaten regular season on his way to a career total of 2,575 rushing yards. The Vols shocking upset loss to Baylor in the 1957 Sugar Bowl occurred after the voting, in which Majors polled second. Five places behind him, the nation’s leader in total offense, Stanford’s John Brodie, gained only gained enough votes to come in a lowly seventh!At Oklahoma, the defending national champions and odds-on favorites to repeat, Bud Wilkinson’s amazing winning streak stretched back to September 1953. Halfback Tommy McDonald finished second nationally in touchdowns with 17. His own teammate, OU halfback Clendon Thomas, denied him the national scoring title by a single TD. McDonald finished third in the voting with 973, just ahead of Oklahoma’s All-American center and linebacker Jerry Tubbs. A few of Tubbs’ 724 total votes would easily have made McDonald coach Wilkinson’s second Heisman winner, but Tubbs and McDonald essentially cancelled one another out. No member of the Sooners' 1956 class claimed the Heisman despite having never lost a single collegiate game.

Finishing fifth on the ballot was a senior running back from Syracuse by the name of Jim Brown. The consensus All-American back had carried 128 times in 1955 for 666 yards and 7 TDs. Although these numbers were impressive they proved insufficient to capture the attention of national writers who doubted the credibility of East Coast, Independent football. ‘Cuse could not claim a single championship or bowl win. Their only post-season appearance, the 1953 Cotton Bowl, had resulted in a 61-6 thrashing at the hands of mighty Alabama. If the Irish had pedigree to spare, the Orangemen could hardly buy it. Since taking over as head coach in 1949 Floyd “Ben” Schwartzwalder had only reached a mediocre 35-27-1 in seven seasons -- all while facing opponents the writers viewed with suspicion. Syracuse football had never produced a single household name at any position. In September 1956 the national spotlight rested on the hopeful Irish, the unstoppable winning streak, and the indomitable Tennessee Vols. Few national fans and pundits spared a thought for lowly Syracuse.

Jim Brown forced his way onto the national stage and into Heisman contention in the same way he forced his way into opposition backfields: with a peerless combination of size, brute force, speed, and startling finesse. Brown racked up 986 yards on 158 carries for 13 TDs and a 6.3 yard average. He was also a crushing middle linebacker and, like Hornung, carried most of his team’s place kicking load. At around 230lb Brown was a monster in the age of mostly white-bred one-platoon football. He routinely stiff-armed hopeless tacklers into the turf, but his game cannot rightly be characterized as a mere matter of raw power. Teammates said Brown used only the energy required for the play at hand. He always conserved his strength for the moment of greatest need. Whenever the situation truly demanded a marathon effort, Brown seemed to have an extra gear and would leave tacklers standing.

Somehow the indefatigable Brown also possessed sufficient surplus energy to letter in track and field, basketball and lacrosse. Brown averaged 15 ppg in basketball his sophomore year and 11.5 ppg his junior year. He contributed in multiple track and field events, routinely making the difference between victory and defeat at meets. He lettered four years in lacrosse, topping the national scoring table his senior season and leading Syracuse to a 10-0 record: its first unbeaten campaign since 1922. The most famous incident of Brown’s illustrious collegiate career occured after his football eligibility expired. On a clear May day in 1957 he competed against Colgate in high jump, winning the event before the Orangemen’s final lacrosse fixture against Army. As Brown attempted a change into his pads some teammates, frantically fearing defeat against their arch-rival, found him in the locker room and begged him to contribute in two other events. Brown placed in javelin and discus before leading the lacrosse team to an 8-6 victory with two goals while still wearing his track shorts. The track and field team triumphed by 13, the exact number of points Brown's performances added.

Somehow the indefatigable Brown also possessed sufficient surplus energy to letter in track and field, basketball and lacrosse. Brown averaged 15 ppg in basketball his sophomore year and 11.5 ppg his junior year. He contributed in multiple track and field events, routinely making the difference between victory and defeat at meets. He lettered four years in lacrosse, topping the national scoring table his senior season and leading Syracuse to a 10-0 record: its first unbeaten campaign since 1922. The most famous incident of Brown’s illustrious collegiate career occured after his football eligibility expired. On a clear May day in 1957 he competed against Colgate in high jump, winning the event before the Orangemen’s final lacrosse fixture against Army. As Brown attempted a change into his pads some teammates, frantically fearing defeat against their arch-rival, found him in the locker room and begged him to contribute in two other events. Brown placed in javelin and discus before leading the lacrosse team to an 8-6 victory with two goals while still wearing his track shorts. The track and field team triumphed by 13, the exact number of points Brown's performances added.Jim Brown suffered in the Heisman race because he did not play a football game truly in the national spotlight until his final appearance, in the 1957 Cotton Bowl. By that point the trophy had been awarded. Had the Downtown Athletic Club waited until after the bowls (as it still doesn’t but absolutely should), voters would have been impressed as Brown carried Syracuse almost single handedly against a TCU team that ranked as undoubtedly the best opponent the Orangemen faced during his collegiate career.

Led by their own All-American, halfback Jim Swink, the Frogs had dominated the Southwest Conference. TCU’s diversified passing attack proved a handful for the Orangemen. The Horned Frogs scored a touchdown in each quarter, three of them on drives of over 60 yards. Of TCU’s 335 total yards, 202 came on 13 complete team passes of 16. The entire Frog team combined for just 133 rushing yards. Brown made 132 alone in reply. He scored the first three Syracuse touchdowns and ground out much of the yardage on the drive late in the fourth quarter that set up a 27 yard TD pass from Chuck Zimmerman to Jim Ridlon.

On Syracuse's first scoring drive, in the second quarter, Brown kick-started a comeback with a searing run of 24 yards. He added 6, 5, and 18 before a 2 yard plunge across the plane – all coming after he set the drive up with a 30 yard kick return from the end zone. From goal line to goal line Brown accounted for 90 of the 100 yards. The run-focused Orangemen made only 3 of 7 passing for 63 on the day, but one of those completions came on a fullback toss from Brown to Ridlon for 20 yards. Brown also added a kickoff return of 46 yards and attempted all four PATs. His play alone would have earned a hard fought tie had Narcico Mendoza not burst through the line to block his third kick. The two-point conversion did not enter college football until 1958. Given the opportunity Brown would surely have been the odds on favorite to tie the game from three yards inside the final two minutes. As it was, his failed PAT attempt made the difference.

There simply has never been a college athlete like Jim Brown. There never will be again. Yet he finished only fifth in the Heisman voting his senior year. Fifth: for the premier award in the sport at which he excelled more than any other. Surely Brown deserved the Heisman?

There simply has never been a college athlete like Jim Brown. There never will be again. Yet he finished only fifth in the Heisman voting his senior year. Fifth: for the premier award in the sport at which he excelled more than any other. Surely Brown deserved the Heisman?In the end Paul Hornung claimed the award – the first player ever to do so without gaining the most first place votes. Hornung polled fewer first place votes than both Johnny Majors and Tommy McDonald. Majors also beat him on second place votes. Brown polled only half of Hornung’s 1,066 total votes, despite gaining only 79 fewer first place votes. Hornung became the only player to claim the Heisman after a losing season. This result still stands out to many as one of the most egregious miscarriages of justice in college football history. Even Notre Dame writers acknowledge that the “Golden Boy” hardly deserved the crown.

Steve Delsohn wrote: “Hornung didn’t deserve it. Not with three touchdown passes and 13 interceptions. And not on a 2-8 team. The Heisman should have gone to Jim Brown. The magnificent Syracuse fullback averaged 6.2 yards a carry, gained 986 yards, and scored 14 touchdowns. But, in 1956, Jim Brown had the wrong color skin.”

In response to such assertions it must firstly be noted that Paul Hornung was an outstanding football player. Voters did not simply look for any old character to palm the trophy off onto because Brown was black. On any ordinary Notre Dame team Hornung would have claimed the Heisman in a cake walk. He starred in football, baseball and basketball at Flaget High School in Louisville, setting statewide records and attracting the persistent attention of Bear Bryant, then head coach at the University of Kentucky. Almost sixty years since he graduated, the Kentucky High School Athletics Association still bestows the annual “Paul Hornung Award” on the state’s outstanding football player.

The “Golden Boy” was an extremely versatile player. In addition to attempting the majority of Notre Dame's passes he was a stand-out defensive back and a considerable rusher, gaining 472 yards on 92 carries as a junior. He also featured as a place kicker and punter. He finished second in Heisman voting as a junior. Ohio State’s Howard “Hop-along” Cassidy claimed the prize with an impressive 964 yards rushing and 15 TDs. Cassidy was a great running back. But Hornung was so much more.

After entering the 1956 season as Heisman favorite Hornung amassed 1,337 yards total offense, second highest in the nation. He added 420 yards rushing and 3 TDs to his passing totals. Many feel that his dire passer ratio of 3 TDs to 13 INTs resulted from the graduation of Notre Dame’s entire 1955 receiving core. Hornung was the sole highlight on a woeful Irish team. In his final collegiate game, a gruelling road test at USC which he played with two sprained thumbs, Hornung accounted for 354 yards total offense, including a 95-yard kick off return for a touchdown. Notre Dame lost.

In the mid-fifties, under the leadership of controversial President Father Theodore Martin Hesburgh, the University of Notre Dame deemphasized football for the only time in its history. Hesburgh sought to reestablish the primacy of the school's academic reputation and did so by very publically reducing football scholarships. Those cut backs began to bite in 1956, leaving the Irish numerically thin and relatively talent starved. Irish fans still argue as to how far Hesburgh’s actions really cost their football team, but head coach Terry Brennan and several former Irish coaches were in no doubt. What is absolutely certain is that 1956 was the historical nadir for Irish football. And in that darkest hour only the star of Paul Hornung shone true to the Notre Dame tradition.

Hornung went on to become a hall-of-fame pro star with the Greenbay Packers. He led the NFL in scoring from 1959 to 1961 and was league MVP consecutively in 1960 and 1961. His 19 points in the 1961 NFL championship game remain the individual record. In 9 seasons as a pro he made 66 of 140 field goals (not a bad record for the era), averaged almost 7 yards per pass attempt, and scored 50 rushing TDS with a 4.2 yards per carry mark.

The legendry Vince Lombardi once gave Notre Dame’s “Golden Boy” the highest possible praise, saying:

“Paul Hornung could do more things than any man who ever played this game.”

No doubt several other players hold manifestly justifiable claims to the 1956 Heisman trophy. But whatever can be said about the controversial award, it is impossible to claim that Paul Hornung was catagorically undeserving.

Race did factor into the 1956 Heisman chase, but not in the sense that many commentators believe. It is hard to conclude that the college football establishment was not prepared for a black Heisman winner when only five years later the same voters granted the award to Ernie Davis, the next 'Cuse running back to wear Brown's jersey number. In fact, the racial barriers that most hurt Brown’s chance of earning college football’s top award lay within his own school.

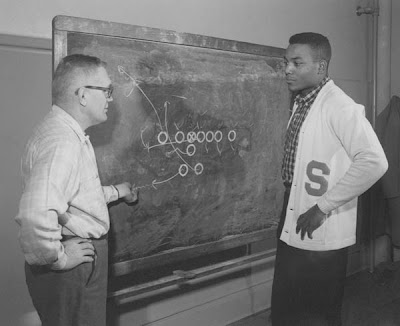

Brown attended Syracuse at the urging of Kenneth Molloy, a prominent alumnus and personal supporter from his hometown of Manhasset, Long Island. Schwartzwalder did not want Brown on his team and only accepted him under pressure from Molloy. Brown did not even have an athletic scholarship his freshman year. Molloy and other local supporters in Manhasset raised money to pay his school fees - a fact Brown only learned later.

Syracuse had already experimented with one black football player. A talented quarterback named Avatus Stone had endured two seasons of dehumanizing treatment before seeking refuge in the Canadian Football League in 1952. Stone was not allowed to eat or room with white teammates. Coaches punished his mistakes disproportionately and forbade him from fraternizing with Caucasian coeds. When Stone protested and reacted with anger, several times striking out physically at coaches and players, he was labeled a troublemaker.

Initially Schwartzwalder told Molloy that he never wanted another black player on his team. They were “too much trouble.” But Brown toughed it out, used his righteous anger to fuel his performances, and played his way onto the team.

Brown faced the same abuse Stone suffered through. He was isolated, ostracized and struggled to rise up the depth chart despite his eminent talent. He saw little playing time as sophomore, entirely because of bigotted animosity from the coaching staff. On several occassion his mentor and ally Roy Simmons, the Syracuse lacrosse coach, talked Brown into staying in school after he resolved to quit.

Brown faced the same abuse Stone suffered through. He was isolated, ostracized and struggled to rise up the depth chart despite his eminent talent. He saw little playing time as sophomore, entirely because of bigotted animosity from the coaching staff. On several occassion his mentor and ally Roy Simmons, the Syracuse lacrosse coach, talked Brown into staying in school after he resolved to quit.Under-utilized on a mediocre team, playing as an Eastern Independent for a coach with an unimpressive track record, Brown’s position entering the 1956 season could hardly have contrasted more starkly with that enjoyed by Paul Hornung. Brown had never played in a bowl. He had not earned national attention as a junior, and he did not play for a fashionable team. The 1955 Orangemen had won only five games to Notre Dame's eight.

Then as now, media relations, program prestige and access to the national TV and radio spotlight decided the Heisman trophy race as much as talent. Ernie Davis won the trophy in 1961 not because the intervening years had wrought a massive racial sea-change in America. They hadn’t. Davis won because Brown’s talent and sheer resolve broke the Syracuse coaches. Schwartzwalder started Davis as a sophomore in 1959. The Orangemen rode his running to an 11-0 season, a Cotton Bowl victory over Texas, and the school’s only national title. By his senior year the eventual Heisman winner was a recognized star on a prominent team with an AP championship in the bank.

The reality of how the Heisman trophy winner is largely selected actually makes Hornung’s triumph an important and satisfying record. Once, if only once, a man on a losing team has earned college football’s highest award for recognition of individual talent. The trophy is supposed to acknowledge the single greatest player in the game. Instead, it has increasingly become an award for the designated leader on the nation’s most successful and fashionable team. It grows more unsatisfying every year.

Were I the sole arbitrator of the annual Heisman race, the 2008 trophy would have gone to Todd Reesing, QB of the 7-5 Kansas Jayhawks. He plays at an unfashionable school but his numbers compare favorably to Sam Bradford, Colt McCoy and Tim Tebow. No player does more with less. Isn’t that what separates individual greats from the herd? And has any player in college football history ever done more with less than Paul Hornung, who in 1956 single-handedly defended the honor and glory of the Notre Dame tradition on the worst Irish team of all time?

When the Downtown Athletic Club of Manhatten first informed John Heisman, one of the great architects and evangelists of the game,

of their intent to name an award for the sport’s outstanding player after him, he protested. Heisman did not want to lend his name to anything that singled out one man in a team game. Compare this view of the sport to current media coverage that elevates Tebow so far above the Gators that his image now eclipses an entire university. Heisman no doubt turns in his grave every time an ESPN commentator recounts the tale of Tebow’s tear-jerking postgame press conference following the famous home loss to Ole’ Miss. Just as Heisman warned, the trophy that took his name fails to represent the root of college football's genius. Our sport's premier award has become a mockery and lies in dire need of reform.

of their intent to name an award for the sport’s outstanding player after him, he protested. Heisman did not want to lend his name to anything that singled out one man in a team game. Compare this view of the sport to current media coverage that elevates Tebow so far above the Gators that his image now eclipses an entire university. Heisman no doubt turns in his grave every time an ESPN commentator recounts the tale of Tebow’s tear-jerking postgame press conference following the famous home loss to Ole’ Miss. Just as Heisman warned, the trophy that took his name fails to represent the root of college football's genius. Our sport's premier award has become a mockery and lies in dire need of reform.Next year, I suggest bestowing it upon the noble and talented leader of a uninspiring sub .500 team.

(Sources: CFB data warehouse; Hornung stats: ESPN Classic on Hornung; Syracuse stats on Brown; Brown’s hoops stats; Mike Freeman, Jim Brown; Steve Delsohn, Talking Irish; SU box score of the Cotton Bowl; http://www.heisman.com/; Vols rush stats; John Devanny, Winners of the Heisman Trophy; Dan Jenkins, Greatest Moments)

Regardless of idle taunts from bitter UT backers, the OU football machine wasn’t built exclusively, or even predominantly, by ‘stealing’ Texan talent. Dozens of Oklahoma raised boys went on to All-American honors. Buddy Burris, Darrel Royal, Eddie Crowder, Billy Vessels, J. D. Roberts, Tommy McDonald, Clendon Thomas, Bill Krisher . . . whoever Bud wanted in the state Oklahoma, Bud got. Wilkinson went 15-2 against in-state rival Oklahoma A&M. The Aggies (now OSU Cowboys) had always struggled to attract top players to Stillwater and had never fared well against the state’s flagship university, but Bud took domination to a new level. His merciless ownership of A&M borders on sadistic bullying. OU has dominated in-state recruiting at almost that level ever since.

Regardless of idle taunts from bitter UT backers, the OU football machine wasn’t built exclusively, or even predominantly, by ‘stealing’ Texan talent. Dozens of Oklahoma raised boys went on to All-American honors. Buddy Burris, Darrel Royal, Eddie Crowder, Billy Vessels, J. D. Roberts, Tommy McDonald, Clendon Thomas, Bill Krisher . . . whoever Bud wanted in the state Oklahoma, Bud got. Wilkinson went 15-2 against in-state rival Oklahoma A&M. The Aggies (now OSU Cowboys) had always struggled to attract top players to Stillwater and had never fared well against the state’s flagship university, but Bud took domination to a new level. His merciless ownership of A&M borders on sadistic bullying. OU has dominated in-state recruiting at almost that level ever since.